International Science Faculty in Saudi Arabia Research Experiences and Challenges

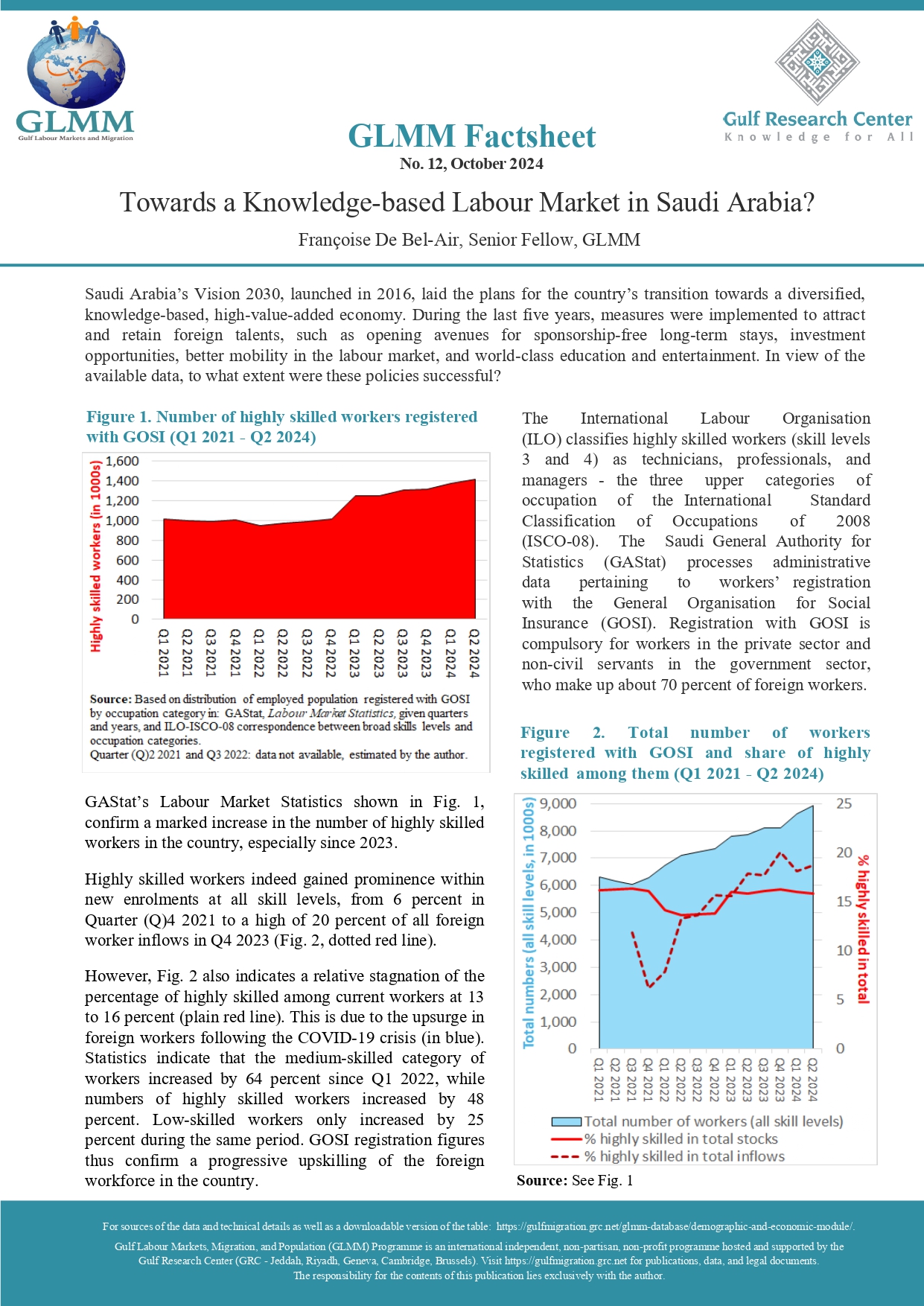

The 30 million foreign nationals residing in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) region make up approximately 52 percent of the total population in the region. This “demographic imbalance” is the result of large immigration -the region hosted 11 per cent of the world’s total migrant stock in 2019 according to UN estimates- and to the quasi-absence of naturalisation of non-Gulf nationals, which recently has been loosened in some countries for distinct groups of foreign nationals.

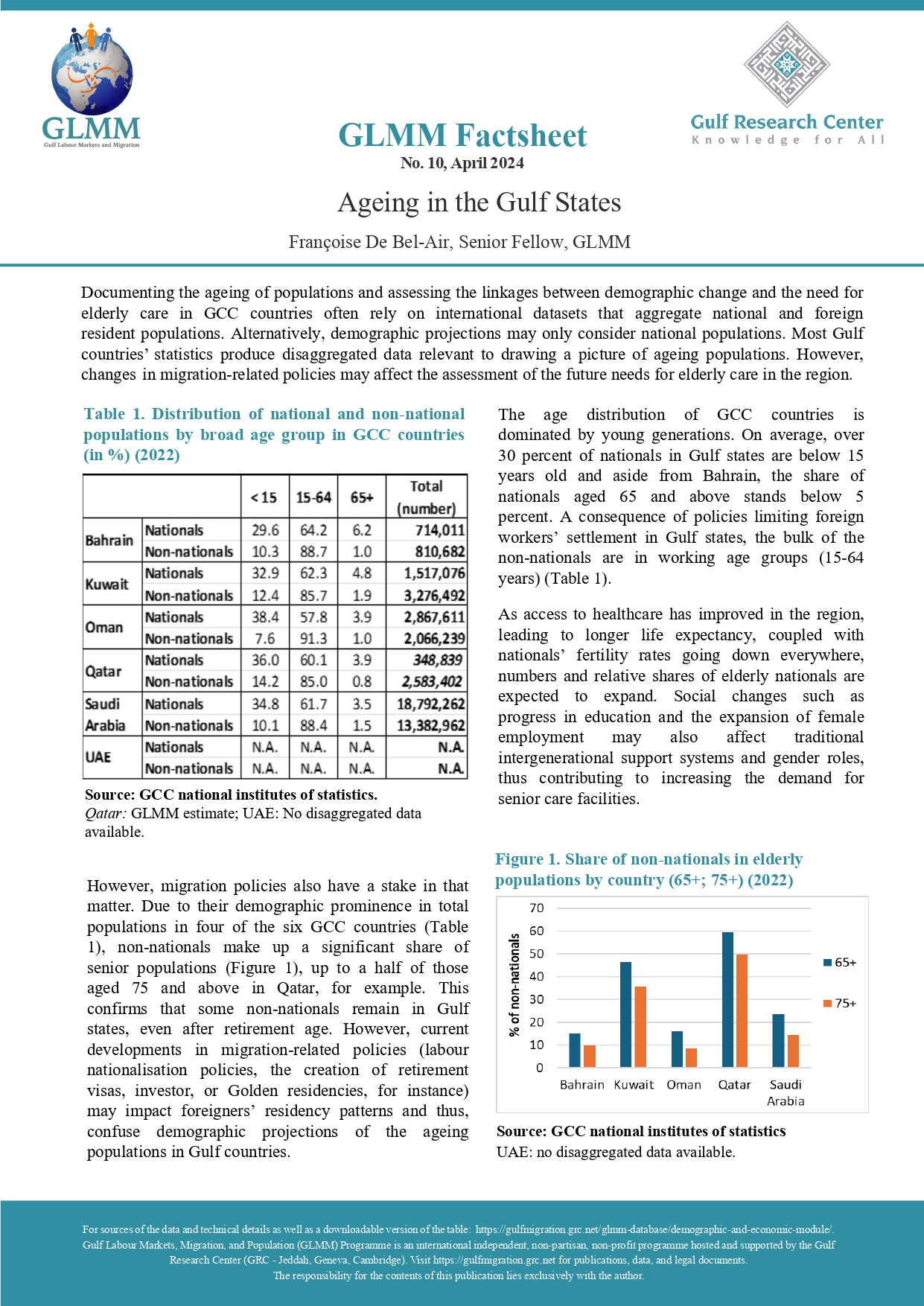

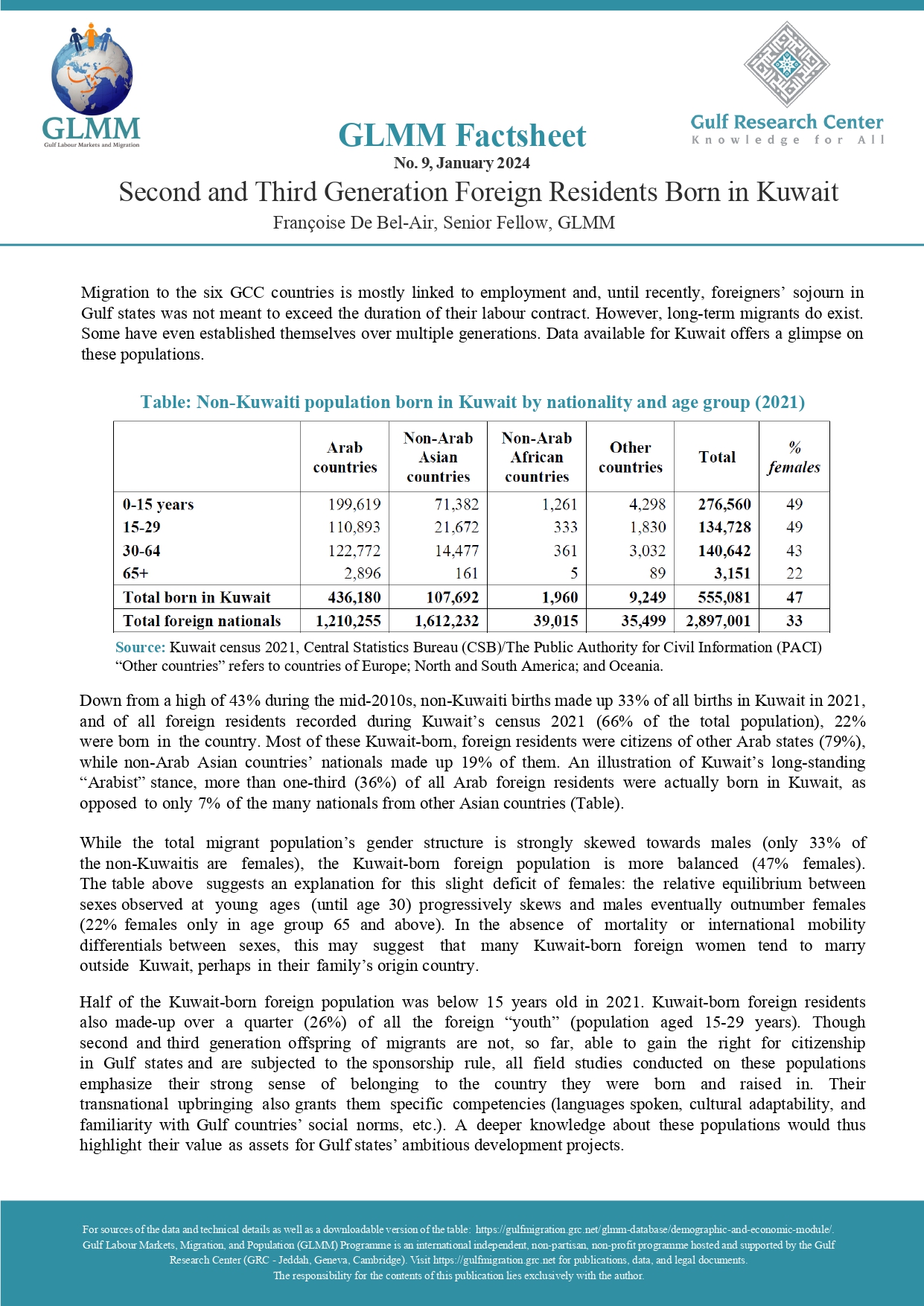

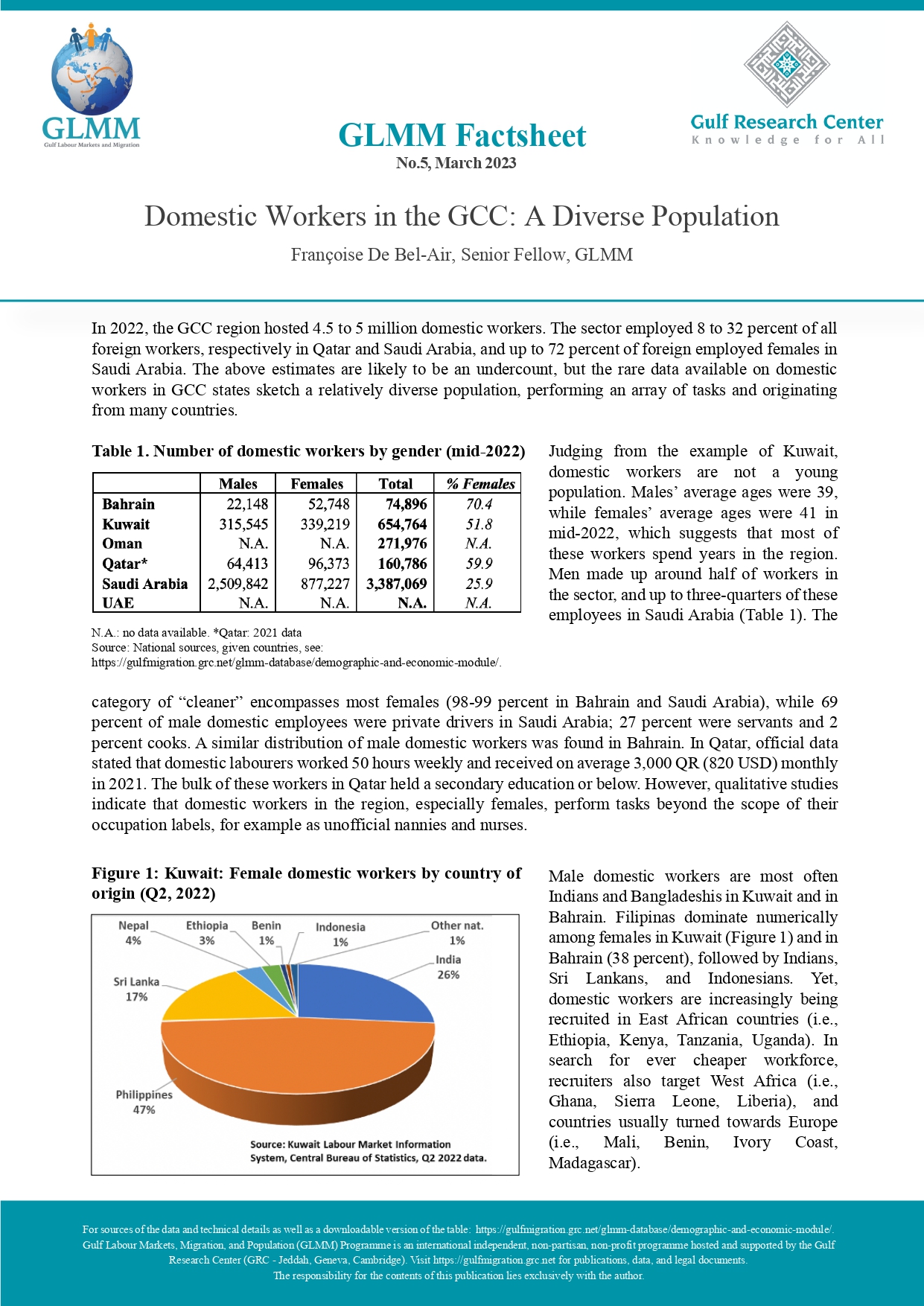

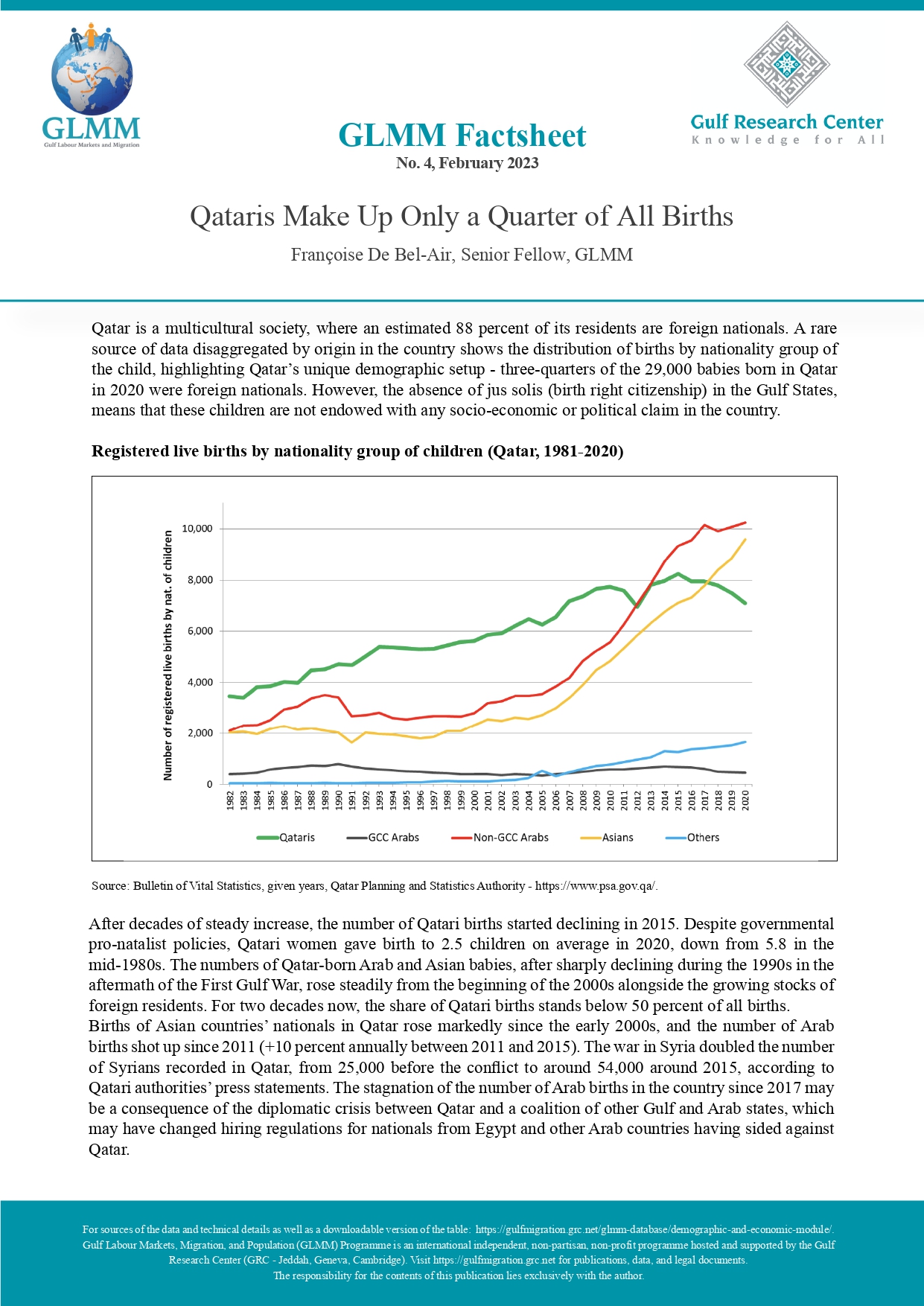

Total population and percentage of nationals and non-nationals in GCC countries (mid-2020)

| Country | Total population | Nationals | Foreign nationals | % Nationals | % Non-nationals |

| Bahrain | 1,472,204 | 713,263 | 758,941 | 48.4 | 51.6 |

| Kuwait | 4,816,592 | 1,442,005 | 3,374,587 | 29.9 | 70.1 |

| Oman | 4,578,016 | 2,719,500 | 1,858,516 | 59.4 | 40.6 |

| Qatar | 2,833,679 | 338,000* | 2,495,679* | 11.8** | 88.2** |

| Saudi Arabia | 35,013,414 | 21,430,128 | 13,583,286 | 61.2 | 38.8 |

| UAE | 9,282,410 | 1,215,996* | 8,066,414* | 13.1** | 86.9** |

| Total | 57,996,315 | 27,858,892* | 30,137,423* | 48.0** | 52.0** |

| Source: National Institutes of Statistics and GLMM’s estimates based on data published by National Statistical Institutes. See the original table in GLMM’s database for more details (https://gulfmigration.grc.net/glmm-database/demographic-and-economic-module/).

* GLMM’s estimate, based on data published by National Statistical Institutes (see original table). ** Ratio is calculated based on population estimates (see original table). |

|||||

In mid-2020, the population of foreign nationals in the Gulf States ranged from 39% in Saudi Arabia to 88% in Qatar. As a consequence, the ratio of nationals (indigenous citizens) to non-nationals (expatriate workers and their dependents) was skewed in favour of the latter in all Gulf states but two, which some perceive as a “demographic imbalance”. This may explain why the UAE and Qatar do not publish total population figures disaggregated by nationality.

Other regions worldwide, such as the EU or North America, which receive large numbers of immigrants, record migrants as “born abroad.” This suggests the integration of foreign residents within the society of the host states, and in the citizenry for those who are naturalized citizens. By contrast, Gulf states do not conceive themselves as immigration countries and record migrants as non-national, temporary expatriate workers (wafidîn). These have little social and no political membership. Conditions for naturalisations are very restrictive; the birth right does not apply, including for Gulf-born, second- or third generation expatriates.

Thus, the unique socio-demographic structure of Gulf societies stems from the opening of Gulf economies to exceptionally large numbers of foreign labourers since the 1950s, coupled with the quasi-closure of Gulf societies to the socio-political integration and in particular, to the naturalisation of non-Gulf nationals.

Therefore, the current “demographic imbalance” is likely to persist unless the policies regarding naturalisation and/or immigration of temporary labour undergo a significant change. Examples of such policies include avenues for long-term settlement in some countries (Saudi Arabia, UAE) and (limited) naturalization (UAE) for specific, small numbers of foreign nationals.